Among my earliest memories as a baseball fan was Willie Mays’ heroics as the SF Giants chased down the Dodgers to force a playoff for the National League pennant. Willie hit a late HR in a 2-1 win on the last day of the 1962 regular season. When the Dodgers lost 1-0 a few minutes later on a Gene Oliver homer, the Giants and Dodgers were tied at 101 wins.

This set up a best-of-three playoff series. In the first game Willie hit two home runs in a Giants’ victory. After a Dodger win in game two, Willie played a pivotal role in a ninth inning rally as the Giants won game three and the pennant.

I was hooked as a Willie Mays fan.

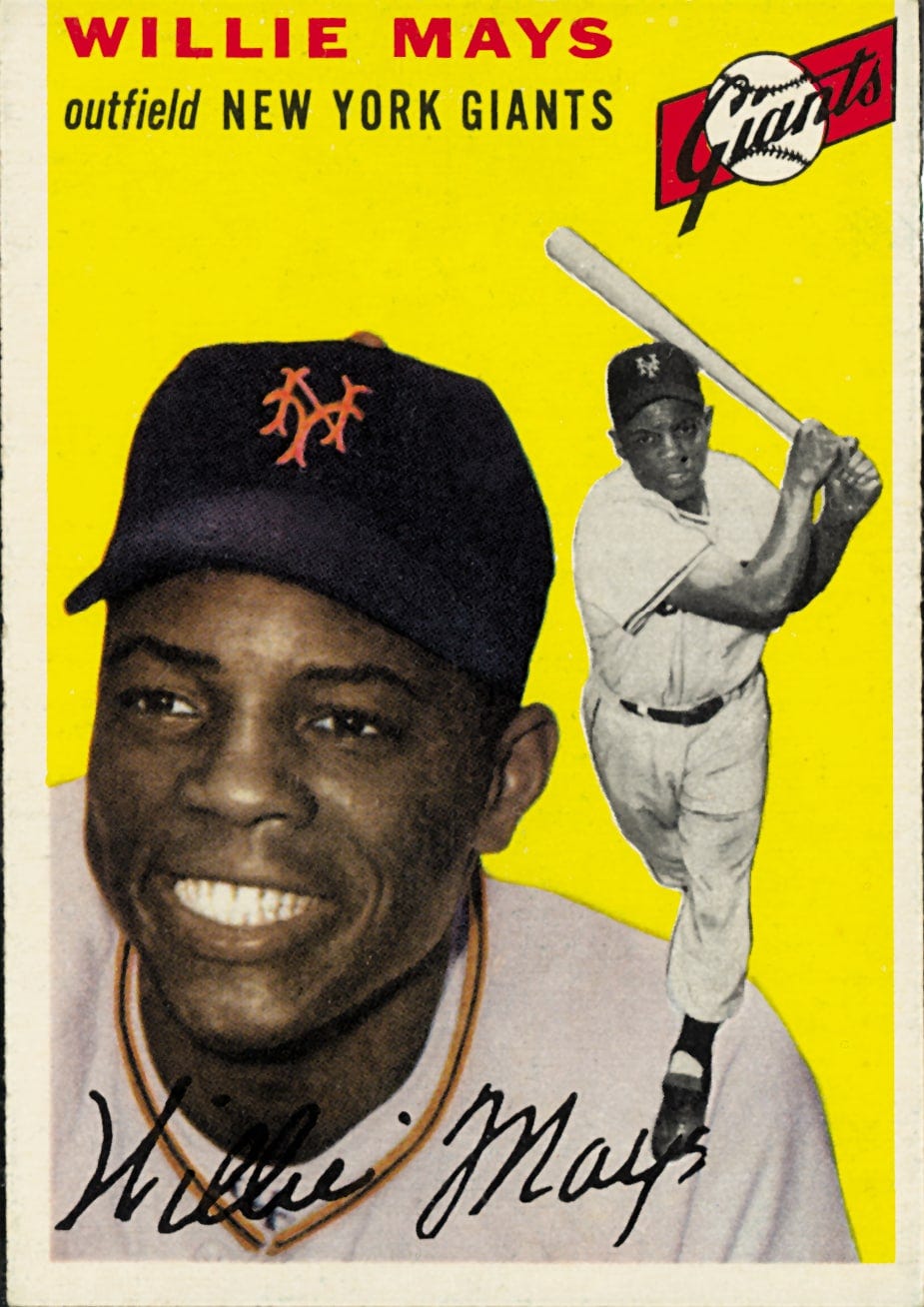

Baseball lost Willie Mays yesterday. America lost an icon and a treasure.

As a ballplayer he was “electrifying.” He could do it all. Run, hit, hit for power, throw, catch…all five tools. But what we remember most is the charisma and timing. Coming through in the key moments. The high-pitched voice and infectious laugh. His obituary in the New York Times reads in part:

Mays compiled extraordinary statistics in 22 National League seasons with the Giants in New York and San Francisco and a brief return to New York with the Mets, preceded by a time in the Negro leagues, from 1948-50. He hit 660 career home runs and had 3,293 hits and a .301 career batting average.

But he did more than personify the complete ballplayer. An exuberant style of play and an effervescent personality made Mays one of the game’s, and America’s, most charismatic figures, a name that even people far afield from the baseball world recognized instantly as a national treasure.

He hit 660 home runs despite losing two of his peak years to the Korean War, and playing most of his home games at Candlestick Park, where the cold temperatures and wind blowing in from LF (Mays hit righthanded) made it very tough on hitters, especially righthand hitters. He led the league in HRs four times, but also led the league in stolen bases four times. Without those lost years and playing in a more friendly park, it is not unlikely that he would have been the one to break Babe Ruth’s HR record. His stats were mind-boggling, and are compiled by the WAPO’s Brian Gross in this article.

But his flair and dash on the bases and his ability to catch anything hit in the air that didn’t leave the park differentiated him from everyone else. As a fielder he’s best known for “The Catch” in the 1954 World Series. I won’t bother to describe it; you can watch it here. You MUST WATCH IT HERE.

Willie won two Most Valuable Player awards (1954 and 1965) but that was by far too few. Ten times he led his league in WAR (Wins Above Replacement…i.e., how many games his team won because of his offense and defense than they would have won with a “replacement level,” or marginal major leaguer). MVP awards are biased toward a player on a pennant winning team, and his Giants, while the winningest team of the ‘sixties, almost always finished second (every season from ‘65-’69) to a revolving cast of teams (mostly the Dodgers and Cardinals). Thus MVP awards usually went to the most important player on the pennant-winning team (although Willies monumental 1965 season led to an MVP despite a second place finish for his Giants, who finished three back of the Dodgers).

But Willie was also the man who received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, as Barack Obama told Willie when they flew together to the 2009 All star Game: “It’s because of giants like Willie Mays that someone like me could think of running for president”…and the kid who would play stickball with the kids in his Harlem neighborhood after a day game or before a night game with the NY Giants at the Polo Grounds.

He was the 17th Black player, following the path forged by Jackie Robinson in 1947. He came to the Giants after a couple of years in the Negro Leagues with the Birmingham Barons. In his first minor league season he was the only Black player in the league. As the Times obituary reports:

In his Hall of Fame induction speech at Cooperstown, N.Y., he recalled one episode in Hagerstown, Md.

“The first night, I hit two home runs and a triple. Next night, I hit two home runs and a double. On the loudspeaker, now, they say, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, we know you don’t like that kid playing center field, but please do not bother him again because he’s killing us.’ I went there on a Friday, they were calling me all kinds of names. By Sunday, they were cheering. And to me, I had won them over.”

Much later in his career (1964) he held the team together after the Giants manager at the time, Al Dark, made some ill-conceived comments to a Newsday reporter saying that his Black and Latin players (that included Orlando Cepeda, the Alou brothers, Willie McCovey, Jim Hart, Jose Pagan and others in addition to Mays) “…are just not able to perform up to the white players when it comes to mental alertness.”

Willie convinced the team to stay together despite Dark, as they were in the hunt….

….A few years back — I think it was in the fall of 2017 — I was playing ball in a 45-and-over league in Baltimore County. Our “fall ball” games were more like sandlot games than our regular season. In the fall we did not have set teams like we did during our April - August schedule. Guys showed up on Sunday morning and we arranged teams based on who was there. One Sunday our captain-for-the-day made up the lineup…he had me batting third and playing CF. I approached him and said: “Gary, I think this is a case of mistaken identity.”

He insisted it wasn’t, and wanted me in those slots. Despite being 67 years old, I jogged out to CF. \

But I didn’t belong there. Willie played CF, and he usually batted third.